An IrishBlog about Ireland including music, video, stories, drama, politics, news, media, twitter, facebook, google buzz, blogger and YouTube

Irish Time

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER | Release Martin Corey

In the Name of the Father Release Martin Corey

international | crime and justice | news report

international | crime and justice | news report  Wednesday June 26, 2013 07:17

Wednesday June 26, 2013 07:17 by Brian Clarke - AllVoices

by Brian Clarke - AllVoices

Release Martin Corey

On 9 February 2005, then Prime Minister Tony Blair issued a public apology for the miscarriages of justice known as the Guilford 4, saying that he was "very sorry that they were subject to such an ordeal and such an injustice", and that "they deserve to be completely and publicly exonerated." If all this injustice happened in an open court, what chance does a 63 year old Irishman like Martin Corey have in a secret court, with secret paid evidence, where he has no idea of charge or length of sentence and is not allowed to defend himself? Giuseppe Conlon went to London, to simply help his son, as any good father would do on hearing of his son's wrongful arrest for terrorist offences, below is the nightmare that followed

To cut a long story short Giuseppe Conlon on his arrival in London was arrested, tortured, framed and very quickly found himself in an English prison. Giuseppe's health deteriorate in Wormwood Scrubs prison where he was eventually serving his sentence for possession of explosives. He died on Jan 23rd 1980, the same day Home Secretary William Whitelaw decided to grant him parole.

Giuseppe maintained his innocence to the end of his life.

On December 1979 Giuseppe’s health who had a chronic chest condition became so serious that he was moved from Wormwood Scrubs prison in London to Hammersmith Hospital. Just over a week later, despite being on oxygen and a drip feed in hospital, he was returned to prison. The British authorities informed his incredulous family, they were afraid that the Irish Republican Army (IRA) would kidnap him. Giuseppe Conlon was again on his return to prison so sick that he was again moved from prison back to hospital as his health continued to worsen. He died on Jan 23rd 1980. On the same day he died, Home Secretary William Whitelaw granted him parole.

Over the years, the cases of the Guildford Four and the Maguire Seven came under increasing legal scrutiny and within range of those seeking human rights, demanding a review of the convictions. On 17 October 1989 it was announced that corruption proceedings would be taken against the police involved in the conviction of the Guildford Four. The Court of Appeal decided that the DPP in 1975 had suppressed scientific evidence, which conflicted with the confessions. On 26 June 1991 the Court of Appeal overturned the sentences but all the family by now had completed their sentences. Afterwards many criticized the court for dismissing most of the grounds of appeal and had simply concluded that the hands of the convicted could have been innocently contaminated with nitro-glycerine.

Gerry Conlon says, "My ordeal goes on. For others the nightmare is just starting,

I am often asked if a grave miscarriage of justice like the Guildford Four's could happen today. Shamefully, it could and it does.

I suffer from nightmares and have done so for many years. Strangely, I didn't have them during the 15 years I in spent in prison after being wrongly convicted, with three others, for the 1975 Guildford and Woolwich pub bombings. It was almost as if I was in the eye of the storm while I was inside, and everything was being held back for a replay later in my life.

Our case is well known now as one of the first of the big miscarriage of justice stories, and I am often contacted by people who, like me, spent many years in jail for something they did not do. People ask whether a case like ours could happen today. Of course it could. I know of innocent people still behind bars and I know there are echoes of what happened to us in cases that are still coming to light today.

What happened to us, after all, is not dissimilar to what happened to Binyam Mohamed, the British resident held for many years in Guantánamo Bay. Like him, we were tortured – guns put in our mouths, guns held to our heads, blankets put over our heads. The case against us was, like his, circumstantial. And like him, we tried to get people to listen to what had happened to us, and it took years before our voices were heard outside.

What has been happening in Britain since 2005 has created the same sort of conditions that helped to lead to our arrest. The same procedures are being followed – arrest as many as you can and present a circumstantial case in the hope that at least some of them will be convicted. The one difference, so far, is that juries seem less inclined to convict. But if there is another series of bombs, who knows if that will still apply?

It is still hard to describe what it is like to be facing a life sentence for something you did not do. For the first two years, I still had a little bit of hope. I would hear the jangling of keys and think that this was the time the prison officers were going to come and open the cell door and set us free. But after the Maguire Seven (all also wrongly convicted) – my father among them – were arrested, we started to lose that hope. Not only did we have to beat the criminal justice system but we also had to survive in prison. Our reality was that nightmare. They would urinate in our food, defecate in it, put glass in it. Our cell doors would be left open for us to be beaten and they would come in with batteries in socks to beat us over the head. I saw two people murdered. I saw suicides. I saw somebody set fire to himself in Long Lartin prison.

The first glimmer of home did not come until my father (Guiseppe Conlon, also wrongly convicted and posthumously cleared) died in prison in 1980. My father's last words were "my death will be the key to your release". That proved to be the case, because that was when a number of MPs started to become involved.

It was a terrible price to pay. What many people do not realise is how difficult it is to have your case reopened. It was in 1979 that I wrote to Cardinal Basil Hume about our case and he came to see me in prison. I remember it well: I had been playing football and I was called in to see him – he looked like Batman in his long cloak and he was great, but it was still another 10 years before we were free – even although the authorities knew full well by then who had carried out the bombings and that it was not us.

Since I came out of prison, I have suffered two breakdowns, I have attempted suicide, I have been addicted to drugs and to alcohol. The ordeal has never left me. I was given no psychological help by the government that had locked me up, no counselling. Since our case there have been perhaps 200 others we have heard about of innocent people being released, Sean Hodgson being the latest, and probably a few thousand others that have not had the publicity. I would say the vast majority have almost certainly had problems with drug addiction, have been estranged from their families and disenfranchised from society – yet they have been offered little in the way of help. The money we received in compensation went quickly as a lot of hangers-on arrived on the scene.

I am 55 now and I was 20 when I was arrested so what happened to us has taken up 35 years of my life. I am now with the girl that I met when I first came out of prison and I owe her an enormous amount of gratitude. Others have not been so lucky. I hope that what happened to us will always act as a reminder to people never to jump to conclusions, whatever the nature of a crime, and never to ignore the people who are now trying to get their voices heard so that the nightmare does not happen to them."

See Indymedia Link Below: Stop the Internment Torture of 63 Year Old Martin Corey

Giuseppe maintained his innocence to the end of his life.

On December 1979 Giuseppe’s health who had a chronic chest condition became so serious that he was moved from Wormwood Scrubs prison in London to Hammersmith Hospital. Just over a week later, despite being on oxygen and a drip feed in hospital, he was returned to prison. The British authorities informed his incredulous family, they were afraid that the Irish Republican Army (IRA) would kidnap him. Giuseppe Conlon was again on his return to prison so sick that he was again moved from prison back to hospital as his health continued to worsen. He died on Jan 23rd 1980. On the same day he died, Home Secretary William Whitelaw granted him parole.

Over the years, the cases of the Guildford Four and the Maguire Seven came under increasing legal scrutiny and within range of those seeking human rights, demanding a review of the convictions. On 17 October 1989 it was announced that corruption proceedings would be taken against the police involved in the conviction of the Guildford Four. The Court of Appeal decided that the DPP in 1975 had suppressed scientific evidence, which conflicted with the confessions. On 26 June 1991 the Court of Appeal overturned the sentences but all the family by now had completed their sentences. Afterwards many criticized the court for dismissing most of the grounds of appeal and had simply concluded that the hands of the convicted could have been innocently contaminated with nitro-glycerine.

Gerry Conlon says, "My ordeal goes on. For others the nightmare is just starting,

I am often asked if a grave miscarriage of justice like the Guildford Four's could happen today. Shamefully, it could and it does.

I suffer from nightmares and have done so for many years. Strangely, I didn't have them during the 15 years I in spent in prison after being wrongly convicted, with three others, for the 1975 Guildford and Woolwich pub bombings. It was almost as if I was in the eye of the storm while I was inside, and everything was being held back for a replay later in my life.

Our case is well known now as one of the first of the big miscarriage of justice stories, and I am often contacted by people who, like me, spent many years in jail for something they did not do. People ask whether a case like ours could happen today. Of course it could. I know of innocent people still behind bars and I know there are echoes of what happened to us in cases that are still coming to light today.

What happened to us, after all, is not dissimilar to what happened to Binyam Mohamed, the British resident held for many years in Guantánamo Bay. Like him, we were tortured – guns put in our mouths, guns held to our heads, blankets put over our heads. The case against us was, like his, circumstantial. And like him, we tried to get people to listen to what had happened to us, and it took years before our voices were heard outside.

What has been happening in Britain since 2005 has created the same sort of conditions that helped to lead to our arrest. The same procedures are being followed – arrest as many as you can and present a circumstantial case in the hope that at least some of them will be convicted. The one difference, so far, is that juries seem less inclined to convict. But if there is another series of bombs, who knows if that will still apply?

It is still hard to describe what it is like to be facing a life sentence for something you did not do. For the first two years, I still had a little bit of hope. I would hear the jangling of keys and think that this was the time the prison officers were going to come and open the cell door and set us free. But after the Maguire Seven (all also wrongly convicted) – my father among them – were arrested, we started to lose that hope. Not only did we have to beat the criminal justice system but we also had to survive in prison. Our reality was that nightmare. They would urinate in our food, defecate in it, put glass in it. Our cell doors would be left open for us to be beaten and they would come in with batteries in socks to beat us over the head. I saw two people murdered. I saw suicides. I saw somebody set fire to himself in Long Lartin prison.

The first glimmer of home did not come until my father (Guiseppe Conlon, also wrongly convicted and posthumously cleared) died in prison in 1980. My father's last words were "my death will be the key to your release". That proved to be the case, because that was when a number of MPs started to become involved.

It was a terrible price to pay. What many people do not realise is how difficult it is to have your case reopened. It was in 1979 that I wrote to Cardinal Basil Hume about our case and he came to see me in prison. I remember it well: I had been playing football and I was called in to see him – he looked like Batman in his long cloak and he was great, but it was still another 10 years before we were free – even although the authorities knew full well by then who had carried out the bombings and that it was not us.

Since I came out of prison, I have suffered two breakdowns, I have attempted suicide, I have been addicted to drugs and to alcohol. The ordeal has never left me. I was given no psychological help by the government that had locked me up, no counselling. Since our case there have been perhaps 200 others we have heard about of innocent people being released, Sean Hodgson being the latest, and probably a few thousand others that have not had the publicity. I would say the vast majority have almost certainly had problems with drug addiction, have been estranged from their families and disenfranchised from society – yet they have been offered little in the way of help. The money we received in compensation went quickly as a lot of hangers-on arrived on the scene.

I am 55 now and I was 20 when I was arrested so what happened to us has taken up 35 years of my life. I am now with the girl that I met when I first came out of prison and I owe her an enormous amount of gratitude. Others have not been so lucky. I hope that what happened to us will always act as a reminder to people never to jump to conclusions, whatever the nature of a crime, and never to ignore the people who are now trying to get their voices heard so that the nightmare does not happen to them."

See Indymedia Link Below: Stop the Internment Torture of 63 Year Old Martin Corey

Related Link: http://www.indymedia.ie/article/103792

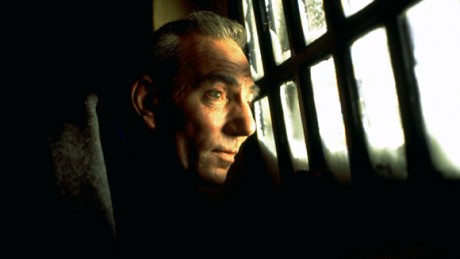

Giuseppe is dead man

Gerry Conlon Talks About His Father Giuseppe

Location:

Ireland

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

FriendFeed

My Blog List

IrishBlog

Twitter follow

Facebook Badge

Facebook Badge

YouTube

Friendconnect

javascript

Subscribe

networkedblogs

Search This Blog

TomsDispatch

Londain Republican

REPORT CHILD ABUSE NOW !

ShareThis

Stakeknife

TomDispatch

irishman

NEWS you WON"T find on the BBC

Stop British Censorship of Irish Dissidents

MUDRACK

The Guardian - inside

SPIKE !

Republican Network for Unity

UnitedIrelander

Irish Blogs

theBestLinks

ORGANIZED RAGE

Irish Freedom News

Slashdot

Blather and Hellfire

Share on Friendfeed

FriendFeed badge

Fenian

STOP CENSORSHIP !

My Headlines

IrishBlog

IrelandYouTube

GAZA HOLOCAUST DENIAL

Podcast Ireland

IRISH BLOG

PROVISIONAL NORTHERN IRELAND

JOHN PILGER

CARNIVAL

INFORMATION CLEARINGHOUSE

HAROLD PINTER NOBEL PEACE

Subscribe Now: Feed Icon

Newstrust

Subscribe Now: Feed Icon

Subscribe via email

My Headlines

My Headlines

Twitter Updates

My Headlines

Ireland Headline Animator

Slashdot

PLEASE RE-TWEET THIS BLOG !

My Headlines

Re-Tweet @ IrishBlogPADDY KAVANAGH'S WHORE http://a2a.me/gfU

Follow Blog

Factual News you definetly won't find on the BBC !

IrelandYouTube Headline Animator

Subscribe Now: Feed Icon

My Blog List

-

Links for 2017-02-22 [del.icio.us] - - Sponsored: 64% off Code Black Drone with HD Camera Our #1 Best-Selling Drone--Meet the Dark Night of the Sky!9 years ago

-

-

Irish Blog: MUSIC FOR PENSIVE VVANKERS - Irish Blog: MUSIC FOR PENSIVE VVANKERS: 'via Blog this' [image: StumbleUpon] My StumbleUpon Page11 years ago

-

Irish Blog: MUSIC FOR PENSIVE VVANKERS - Irish Blog: MUSIC FOR PENSIVE VVANKERS: 'via Blog this'11 years ago

-

Irish Blog: MUSIC FOR PENSIVE VVANKERS - Irish Blog: MUSIC FOR PENSIVE VVANKERS: 'via Blog this'11 years ago

-

-

BOYCOTT BRITISH GOODS ReTweet See Link for Details http://bit... on Twitpic - BOYCOTT BRITISH GOODS ReTweet See Link for Details http://bit... on Twitpic: 'via Blog this'12 years ago

-

RT BOYCOTT BRITISH BRUTISH HUMAN RIGHTS CRIMINALS http://bit... on Twitpic - RT BOYCOTT BRITISH BRUTISH HUMAN RIGHTS CRIMINALS http://bit... on Twitpic: 'via Blog this'12 years ago

-

BBC BRITISH BUGGER CHILDREN World Service http://irishblog-irelandblog.blogspot.com/ rt #BBC - BBC BRITISH BUGGER CHILDREN World Service http://irishblog-irelandblog.blogspot.com/ rt #BBC: BBC BRITISH BUGGER CHILDREN World Service http://irishblog-...13 years ago

-

WOMEN DYING IN BRITISH CONCENTRATION CAMPS - CARE2SHARE ! htt... on Twitpic - WOMEN DYING IN BRITISH CONCENTRATION CAMPS - CARE2SHARE ! htt... on Twitpic Peaceful protesters worldwide are now met with police wearing body armour, ...13 years ago

-

-

INDYMEDIA IRELAND DRIBBLES FROM BOTH SIDES OF ITS MUBARAK MOUTH - Irish Blog: INDYMEDIA IRELAND DRIBBLES FROM BOTH SIDES OF ITS MUBARAK MOUTH15 years ago

-

-

-

Followers

Blog Archive

- ► 2012 (409)

.jpg)